In a solar system called TRAPPIST-1, 40 light years from the sun, seven Earth-sized planets revolve around a cold star.

Astronomers obtained new data from the James Webb Space

Telescope (JWST) on TRAPPIST-1 b, the planet in the TRAPPIST-1 solar system

closest to its star. These new observations offer insights into how its star

can affect observations of exoplanets in the habitable zone of cool stars. In

the habitable zone, liquid water can still exist on the orbiting planet's

surface.

The team, which included University of Michigan astronomer

and NASA Sagan Fellow Ryan MacDonald, published its study in the journal The

Astrophysical Journal Letters.

"Our observations did not see signs of an atmosphere

around TRAPPIST-1 b. This tells us the planet could be a bare rock, have clouds

high in the atmosphere or have a very heavy molecule like carbon dioxide that

makes the atmosphere too small to detect," MacDonald said. "But what

we do see is that the star is absolutely the biggest effect dominating our

observations, and this will do the exact same thing to other planets in the

system."

The majority of the team's investigation was focused on how

much they could learn about the impact of the star on observations of the

TRAPPIST-1 system planets.

"If we don't figure out how to deal with the star now, it's going to make it much, much harder when we look at the planets in the habitable zone—TRAPPIST-1 d, e and f—to see any atmospheric signals," MacDonald said.

A promising exoplanetary system

TRAPPIST-1, a star much smaller and cooler than our sun

located approximately 40 light-years away from Earth, has captured the

attention of scientists and space enthusiasts alike since the discovery of its

seven Earth-sized exoplanets in 2017. These worlds, tightly packed around their

star with three of them within its habitable zone, have fueled hopes of finding

potentially habitable environments beyond our solar system.

The study, led by Olivia Lim of the Trottier Institute for

Research on Exoplanets at the University of Montreal, used a technique called

transmission spectroscopy to gain important insights into the properties of

TRAPPIST-1 b. By analyzing the central star's light after it has passed through

the exoplanet's atmosphere during a transit, astronomers can see the unique

fingerprint left behind by the molecules and atoms found within that

atmosphere.

"These observations were made with the NIRISS

instrument on JWST, built by an international collaboration led by René Doyon

at the University of Montreal, under the auspices of the Canadian Space Agency

over a period of nearly 20 years," said Michael Meyer, U-M professor of

astronomy. "It was an honor to be part of this collaboration and

tremendously exciting to see results like this characterizing diverse worlds

around nearby stars coming from this unique capability of NIRISS."

Know thy star, know thy planet

The key finding of the study was the significant impact of

stellar activity and contamination when trying to determine the nature of an

exoplanet. Stellar contamination refers to the influence of the star's own

features, such as dark regions called spots and bright regions called faculae,

on the measurements of the exoplanet's atmosphere.

The team found compelling evidence that stellar

contamination plays a crucial role in shaping the transmission spectra of

TRAPPIST-1 b and, likely, the other planets in the system. The central star's

activity can create "ghost signals" that may fool the observer into

thinking they have detected a particular molecule in the exoplanet's

atmosphere.

This result underscores the importance of considering stellar contamination when planning future observations of all exoplanetary systems. This is especially true for systems like TRAPPIST-1, since it is centered around a red dwarf star that can be particularly active with starspots and frequent flare events.

"In addition to the contamination from stellar spots and faculae, we saw a stellar flare, an unpredictable event during which the star looks brighter for several minutes to hours," Lim said. "This flare affected our measurement of the amount of light blocked by the planet. Such signatures of stellar activity are difficult to model but we need to account for them to ensure that we interpret the data correctly."

MacDonald played a key role in modeling the impact of the

star and searching for an atmosphere in the team's observations, running a

series of millions of models to explore the full range of properties of cool

starspots, hot star active regions and planetary atmospheres that could explain

the JWST observations the astronomers were seeing.

No significant atmosphere on TRAPPIST-1 b

While all seven of the TRAPPIST-1 planets have been

tantalizing candidates in the search for Earth-sized exoplanets with an

atmosphere, TRAPPIST-1 b's proximity to its star means it finds itself in

harsher conditions than its siblings. It receives four times more radiation

than the Earth does from the sun and has a surface temperature between 120 and

220 degrees Celsius.

However, if TRAPPIST-1 b were to have an atmosphere, it

would be the easiest to detect and describe of all the targets in the system.

Since TRAPPIST-1 b is the closest planet to its star and thus the hottest

planet in the system, its transit creates a stronger signal. All these factors

make TRAPPIST-1 b a crucial, yet challenging target of observation.

To account for the impact of stellar contamination, the team

conducted two independent atmospheric retrievals, a technique to determine the

kind of atmosphere present on TRAPPIST-1 b, based on observations. In the first

approach, stellar contamination was removed from the data before they were

analyzed. In the second approach, conducted by MacDonald, stellar contamination

and the planetary atmosphere were modeled and fit simultaneously.

In both cases, the results indicated that TRAPPIST-1 b's spectra could be well matched by the modeled stellar contamination alone. This suggests no evidence of a significant atmosphere on the planet. Such a result remains very valuable, as it tells astronomers which types of atmospheres are incompatible with the observed data.

Based on their collected JWST observations, Lim and her team

explored a range of atmospheric models for TRAPPIST-1 b, examining various

possible compositions and scenarios. They found that cloud-free, hydrogen-rich

atmospheres were ruled out with high confidence. This means that there appears

to be no clear, extended atmosphere around TRAPPIST-1 b.

However, the data could not confidently exclude thinner

atmospheres, such as those composed of pure water, carbon dioxide or methane,

nor an atmosphere similar to that of Titan, a moon of Saturn and the only moon

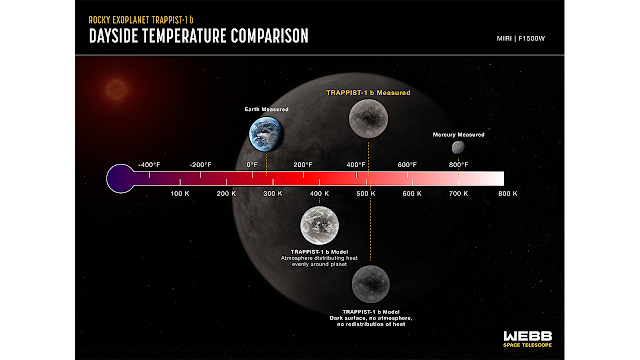

in the solar system with a significant atmosphere. These results, the first

spectrum of a TRAPPIST-1 planet, are generally consistent with previous JWST

observations of TRAPPIST-1 b's dayside seen in a single color with the MIRI

instrument.

As astronomers continue to explore other rocky planets in the vastness of space, these findings will inform future observing programs on the JWST and other telescopes, contributing to a broader understanding of exoplanetary atmospheres and their potential habitability.